The ‘Swahili term rungu [Kalenjin: rungut] refers to the clubs traditionally carried by men in many parts of Kenya. The term has been adopted into East African English: rungu, rungus. [In the English literature about South Africa they are called knobkerries.] While the classic form is a weapon, used as a hand-held club or thrown, they take many forms, indeed are often very individualized. For middle-aged and older men, i. e. elders, their use is symbolic, as statements of male authority, a baton, a scepter.

In 1966 when the thick mud of the rainy season made foot travel difficult, and I started carrying a cane for balance, one of my Kipsigis friends said “Good, Robert. Now you won’t be walking around empty-handed like a woman.” In 1966 I was at a baraza, a meeting of the household heads in the local community to discuss a government proposal. One man rose to address the assembly of elders, seated in a tight group on the grass, then paused and said to his friend “lend me your stick; I can’t talk without one in my hand.”1. Taita Towett (Taaitta Toweett), the leading Kipsigis politician in the early days of the Kenyan Republic, famously carried a rungu, along with his English leather briefcase, into Parliament in Nairobi.

There is, of course, a gestural grammar associated with carrying a rungu, most obviously in these examples:

assertion

threat

conciliation

The top rungu was bought from a Maasai moran, a young unmarried man or “warrior”, at Ngorengore, which in 1965 was little more than an intersection of dusty roads in northwestern Narok District. It is the classic “working model” – stout, with a heavy club end – lethal if used as a weapon. The knob is briar wood from the root structure of a plant (Erica Arborea) and the handle is the trimmed down stem.

The lower specimen was a gift to me from Arap Bartembwet2), a friend in the community which was the focus of my field research. The rungu is well polished from years of handling. Although the knob is dense and heavy, the stem is thin and brittle; this rungu is strictly for show.

I purchased the top specimen from a middle-aged man who was carrying it in the town of Sotik (that’s the colonial name, which means the people of Sot; locals referred to the town as Chemagel). It is carved from a piece of wood to make the end resemble a briar knob. While it would still be effective as a club, it is clearly more of a baton of status than a weapon.

I purchased the lower specimen from a curio shop in Nairobi in 1995. It struck me as a classic example, and is the rungu I carried in the Kipsigis area in 1995 and 1996 when I was leading a UN summer study abroad program and we stayed with families in Itembe for a few days.

These two were purchased, but I can’t remember their source, quite possibly in local markets. The upper one is unusual in having an incised decoration. I do not think it is from the Kalenjin area. It is made from a local dense black wood, possibly ebony.

The lower specimen is a classic shape. When I acquired it, it was new and, like a new baseball glove, had not been “broken in” with handling and hand oil.

This is one of three that I found at a tourist stand at the Sportsman Inn in Nanyuki in 1996. They were similar but not identical in the stained decorations that suggest zebra, giraffe, and leopard. This style of decoration was new then and was used on wooden mugs and other items aimed at the tourist market, but these are the only rungus I saw like this (and I never saw a Kenyan carrying something decorated in this way). I have kept this one for myself, gave another to my adoptive ‘brother’ Kimabwai arap Ng’asura3 when I stayed with him a week later, and finally gave the third to my brother-in-law in Charleston.

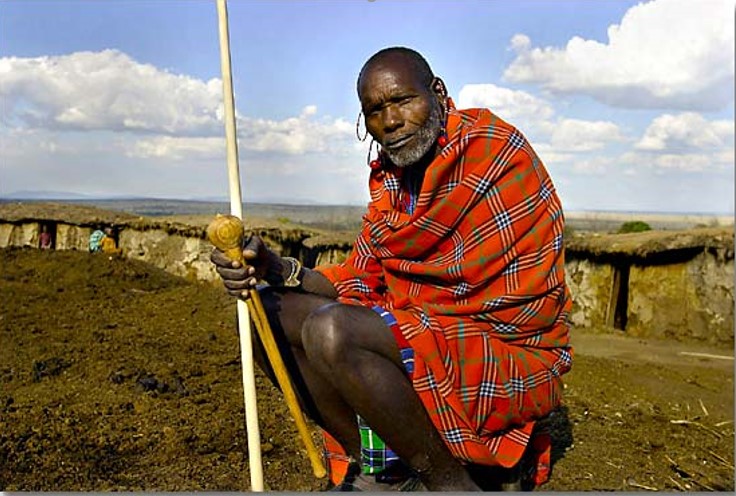

These two are the most unusual items in the collection. Instead of a wooden knob, the upper one has a small metal gear (well-worn and probably discarded from its original use, probably some piece of agricultural equipment). I have seen just a couple rungus being carried that are similar (with a bit larger and sharper gears). I think it is a wonderful example of innovation combining tradition with modernity. I acquired this one in the town of Nanyuki in 1996. I was walking toward the post office when two men came out, an elderly man, perhaps in his late 60s, and his companion, about a generation younger. They were clearly from a rural area. They were wearing sandals, and shorts and the elder wore a shuka (a cloth tied over his right shoulder) instead of a shirt. He had stretched ear lobes. The old man was carrying this rungu. I greeted them in ‘Swahili and struck up a conversation 4 and ended up buying this composite rungu from the elder. It strikes me as a wonderful merger of tradition and twentieth century ‘development’.

The lower rungu is utterly unique in my experience. It was a gift to me from Kimabwai arap Ng’asura after I had presented him with one of the stained rungus discussed above. He said it was from the Congo, but would add nothing else. I sensed that it made him uneasy and he seemed almost relieved to pass it on to me.

The upper specimen was purchased from a small curio shop on a back street in Nairobi in 1996. It was said to be of Kamba origin. Clearly this is a senior elder’s baton.

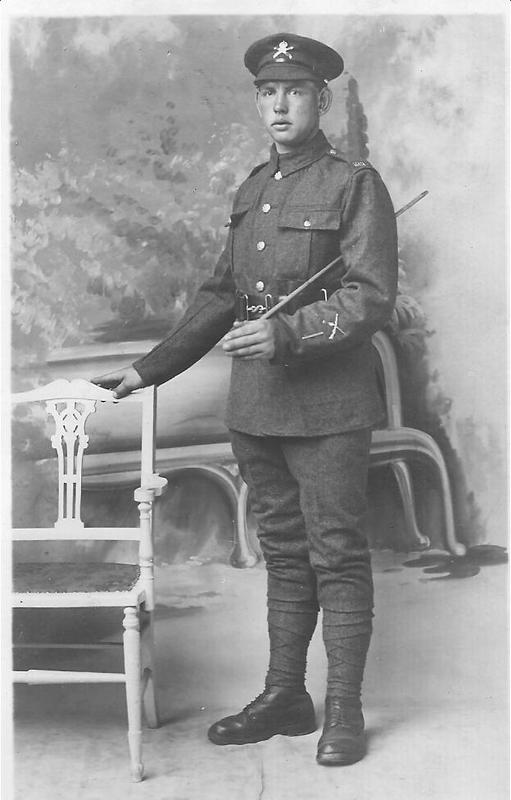

One of the students in the group that year wrote an interesting essay about the confluence of rungus and the British “swagger sticks” which officers in the Kenyan Army and National Police carry.

The larger club shown above is from the Maasai. I do not remember where I got it. Unlike all the others, it is made of relatively light wood. As the photo below shows, it matches a Maasai cattle stick which I purchased at the curio shop in the Norfolk Hotel in Nairobi in 1996.

Both ends are finished in the same manner:

The cattle stick is of dense wood and measures a yard long. It is common for a Maasai herdsman to carry both a stick and a club, usually in the same hand. The cattle stick is not tapped along the ground when walking, though it may be used with an end on the ground as a prop to lean against, particularly when standing on one foot, a characteristic posture known in the early ethnographic literature as Die Nilotenstellung.

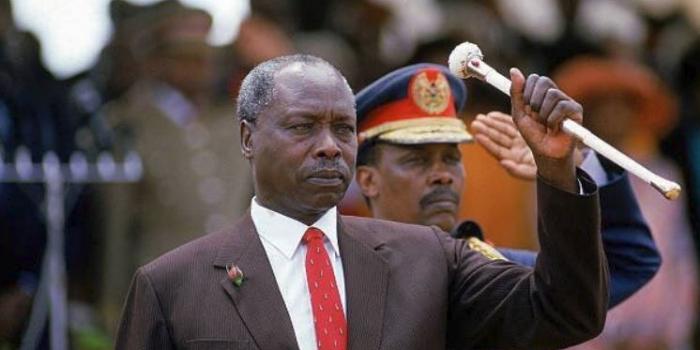

Kenya's Second President, Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi during a state function

1 An interesting parallel, on another social level, is described in the article which is the source of picture E, above: "Queen's Event Moi Refused to Attend Without His Rungu".

2 Arap = son of, bar = kill, tembwet = the valley. Arap Bartembwet, probably in his late 60s at the time, had two wives, the elder of which had taken a neighbor’s daughter as her bride/daughter-in-law. This arrangement is called kotunji toloch, described in detail in my paper A Kipsigis Cattle Dispute.

3 His first name, Kimabwai means ‘the boy born just outside the house (near the mabwaita, th family shrine, a post decorated for rituals). Ng’asura was one of the adult nicknames of his father, Kirichu arap Torgoti; Kimabwai's patronym, Arap Ng'asura, means son of the outspoken man.

4 My conversation outside Nanyuki Post Office in 1996 with an elder who sold me the gear-headed rungu:

He stopped and returned the greeting and I shook hands with him and his companion.

I then asked in Kalenjin: I Kalenjini? Are you Kalenjin?

He paused for a moment, recognized what I must have been asking, and replied Sambur [I am Samburu].

I then switched back into my rough ‘Swahili: Pole, Mzee, sijui KiMaa, lakini ninaweza kusema KiSwahili kidogo. (Sorry, elder, I don’t know the Maasai language but I can speak a bit of ‘Swahili). [KiMaa for the Maasai language was a bit of a guess; I hope I got that right; the Samburu are an offshoot of the main Maasai group].

The rest of the conversation continued in “up-country” ‘Swahili.

I went on to say that I liked his rungu and I had not seen many like his [meaning with a metal head]. Would he show it to me?

He handed me the rungu, with a rather quizzical look. I admired it and handed it back. Since he was obviously wondering what I was all about, I went on to explain that I was a teacher in my home country.

Oh yes, he said, shaking it in a mock threat, this would be very good with bad children in school.

No, no, I said. I don’t want to hit anyone. I want to teach them about the people in Kenya.

He seemed to understand that. I asked him if he would be willing to sell it to me so I could show it to my students back home. He looked at his companion who shrugged. I asked him to name his price. He did, and I agreed with haggling. [I don’t remember the price, but it was the equivalent of a few dollars, and not unlike prices in the tourist market. On reflection, I would have paid more, but I didn’t think to offer that at the moment, and I think it might have been insulting to suggest it.] So I paid what he asked, and we shook on the deal and agreed everything was square (“sawe sawe”).

A http://www.blackmalaika.com/arts-and-crafts/maasia-wear/

B htps://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/96826-the-swagger-stick/page/2/

C https://www.pinterest.com/pin/515943701034097493/

D ?

E https://www.kenyans.co.ke/news/47656-when-mois-rungu-caused-tension-his-closest-aides