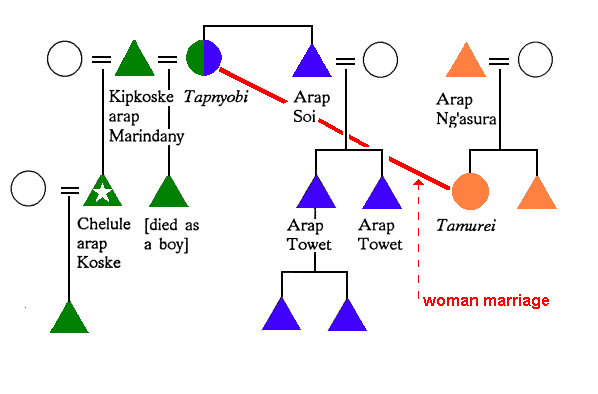

Chelule's father, Kipkoske arap Marindany, had had three wives; Chelule's mother was the first. Being the favorite son of the favorite wife, Chelule continued to live with his parents as a grown man. They lived in Sot, the southern part of the district. The third wife, Tapnyobi, lived about 25 miles to the north in Bureti. Tapnyobi had only one son, and he died as a boy or young man who had not yet married.

Arap Marindany consulted with his sons, a few years later, and decided that Tapnyobi, now an old woman, should marry a young woman, i.e. take on a daughter-in-law in an arrangement known as kotunji toloch1. It was agreed among them that Chelule would be the genitor of this young woman's children (the kipkondit2). They also decided that Chelule would contribute one of his personally owned cows to the marriage payment, an animal which he had seized in a raid against the neighboring Gusii tribe. A suitable family was chosen, and marriage negotiations were conducted by Tapnyobi's brother, Arap Soi (since he lived near the prospective bride's home in Bureti) on behalf of his sister and her husband. The negotiations were successful; Tapnyobi would marry Tamurei, the daughter of Kiplang'at arap Ng'asura, when Tamurei emerged from initiation seclusion.

When Arap Ng'asura came to Sot to collect the cow which Chelule was to contribute, the animal became nervous and ran off. After she was captured, Chelule lent Arap Ng'asura another of his personal cattle to drive with the marriage cow to help calm her down.

Later, when Tamurei arrived in Sot, Chelule discovered that she had sores on her chest. She said that they had developed while she was in seclusion. Chelule sent her back to Bureti, saying that he did not care to become infected. However, he never asked her father to dissolve the marriage.

Chelule heard, years later, that Tamurei had died childless. By then her father, Arap Ng'asura, had died also. Chelule therefore asked Arap Ng'asura's sons to return the cattle paid for Tamurei's marriage. They explained that there had been a crop failure in their area and they had been forced at the time to trade his cow (the one from Gusii) for flour. However, they returned the other marriage cattle and compensated Chelule for his one cow with a number of goats, to his satisfaction. When he inquired about the second cow, the one he had given, not in marriage but on loan, he was told that it had died after having two calves, one of which was still alive. So he took that calf along with the other cattle and goats, and started for home.

On his way he met Arap Soi's sons, Arap Towet and his brothers, who begged him to leave a cow with them as they had also suffered from the crop failure. He agreed, noting that the grazing in their community was particularly good. Chelule left them his own cow, the calf of the one previously lent to Arap Ng'asura, and returned to his home in Sot in the south.

Many years later Chelule heard that the calf that he had left with the Arap Towets had died. He sent word to them asking for the animal's hide. Nothing happened.

After repeated demands from Chelule, Arap Towet came to Sot and presented Chelule with a counter-claim, saying that there had been an outstanding debt of one cow left over from the marriage between Chelule's father, Arap Marindany, and Arap Soi's sister, Tapnyobi; the chebletiot (literally [with feminine prefix} the last one). This cow is traditionally retained by the groom's family until the marriage has produced a child. Chelule dismissed the claim out of hand, saying that there was no way to reopen the deal and trace such a story since all of the people involved, who were of his father's generation, were now dead. Chelule added that his father had never mentioned any such debt to him (the favorite son and executor of his father's estate), nor had he heard it discussed between his parents. To top off his argument, he pointed out to Arap Towet that Tapnyobi had been the type of woman who would say anything when she lost her temper, and that if there really had been such a debt she would have flaunted it before her husband at some point during one of her outrageous tirades. Angered by that very pointed response, Arap Towet threatened to take his claim to the African Native Court (i.e. before the government "chief'). Chelule told him to go ahead, saying that he would be glad to go tell the whole story if summoned.

Arap Towet and his brothers never followed up on their threat, but Chelule took it as a challenge and redoubled his determination to recover his cow. From time to time he sent one of his many sons (he had had five wives) to the Arap Towets in Bureti to ask about the cow. They were told each time that the animal had died. Chelule suspected that the cow was being concealed in another man's herd as a loan.

The cow is killing people!

Finally, when Chelule was in his 80s, one of the younger Arap Towet brothers came to Chelule and confessed that they had, in fact, concealed the cow. The younger Arap Towet explained that as a result of this sin, several small children in their families had died. "Bare bik teta" was Arap Towet's summary of their pitiful state: "The cow is killing people." Arap Towet asked Chelule's forgiveness and pleaded with him to accept whatever cattle he wanted in compensation, and to hold a ceremony to express his satisfaction that the matter had been properly settled (in which Chelule would bless the various Arap Towets by spraying beer on them and thus signal the end of their divine punishment). However, when Chelule pressed for information about the particular cow and her calves, Arap Towet hesitated. Although he kept promising full repayment, he did not answer Chelule's questions directly.

Chelule knew that several of the grandsons of Arap Soi had married by now, and he now worried that his cow and her calves had probably been given away quite improperly in marriage payments (cattle being held on loan should never be transferred to a third party). Chelule concluded that his cows were probably no longer under the control of the various Arap Towets.

Chelule therefore sent his favorite son, Arap Chelule, to Bureti to find out more about the situation. He instructed his son not to go directly to Arap Towet's homestead, but to make inquiries in the neighborhood. Arap Chelule went to Arap Towet's area in Bureti. There he found a man of his own clan, Arap Bii, who lived in Arap Towet's community. Although Arap Bii was Arap Towet's neighbor, and would not normally have shared local information with a stranger, he was also Arap Chelule's "brother" and was therefore willing to give him full details concerning the number of calves born to the cow in question while it was at Arap Towet's homestead. Arap Chelule's newly found kinsman added that he was glad to help since the cow had been causing a great deal of suffering. In his opinion, Arap Chelule's family would be doing these people a great service if he agreed to accept compensation.

Arap Bii however was pessimistic. In addition to the several marriages that had taken place among arap Soi's grandsons, one of these young men had recently killed another man. As a result the dead man's kinsmen had seized several cattle from Arap Towet and his brothers. Thus Arap Bii doubted that Arap Chelule would be able to recover the cattle in question, or possibly even others in their place. Arap Chelule replied that the original cow had been borrowed by his father from another man in Sot, a white lie which underscored his resolve in the matter without revealing any of the details behind his father's adamant ideas on the matter (or his own problems in dealing with the old man).

Arap Chelule then returned home and made a full report to his father. They were at an impasse. The Arap Towets had admitted guilt but not acted on it. Chelule, a man who had outlived the pre-colonial world, refused nonetheless to dismiss the moral tenets by which he had been raised; he would not accept any cattle other than the direct offspring of the one he had lent decades earlier. Arap Towet and his relatives were unable recover these particular animals and seemed to lack both the moral resolve and the business skills to live up to their promises of others in compensation. Chelule did not know if his sons would ever see any cattle from this matter, but he feared that even if they accepted substitutes, it would not be good enough to set things right.

Chelule died about a year after telling me of this problem. I believe the matter was still unresolved.

- 1This practice was unfortunately labeled "woman marriage" in the colonial literature. Kotunji toloch literally translates as to marry ko-tun someone -ji, or -chi [as a] house post toloch - the center post supporting the main rafter beam inside a house ('someone' here implies a bride; in the Kalenjin language, men marry women, women are married by men). The practice was still common during my research in the 1960s. In traditional practice, it is an arrangement for an old woman, beyond child-bearing years, who never had a son survive to take a wife. Acting as an agent of her husband's patriline, the old woman stands in for a non-existent groom in a marriage ceremony which then provides her with a daughter-in-law who will hopefully see to her mother-in-law's care in her old age. Most significantly, in every case for which I had information, kotunji toloch marriages occurred in families in which the elder was still alive, and had at least one other wife who had adult sons. For the elder, such an arrangement is clearly an attempt to redress the imbalance caused by a lack of a male heir which threatens the extinction of that branch of the family. Hopefully the daughter-in-law will provide sons who will be the patrilineal grandsons of the old man. Since pastoral families are herding businesses, and with the house-property complex each wife's "house" is a separate franchise, the phrase kotunji toloch is a metaphor for shoring up a "house" in danger of collapse.

- 2 husband surrogate, literally male supervisor: kip- the male prefix, kondo eye. Widows remain married; they do not remarry. A woman widowed during her child-bearing years is assigned a kipkondit. If she has more children they will be sons and daughters of her deceased husband.